Japonisme in Fine Art is characterized by the integration of Japanese symbolism, spirituality, motifs, and concepts into the work of European art and design. Réhahn’s newest series “Memories of Impressionism” uses principles from this pinnacle movement in art history to dig into the intersections of cultures and art forms in order to create a new aesthetic vision – Impressionist Photography.

An obsession with Japanese arts and crafts took hold in Europe in the 1860s after Japan reestablished trade with the rest of the world. It set off a revolution in the art world, which still resonates today. Without Japonisme, the Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, Expressionist, and Aesthetic Movements could never have existed. Painters such as James McNeill Whistler, Claude Monet, Degas, and Van Gogh—who adapted principles from Japanese art into their own visions—were able to tear down centuries-old rules about what makes a piece of Fine Art have value. Ripples from this shift continue even today within the work of Réhahn, who has put his own mark on the style.

What is Japonisme?

For more than 200 years, from 1640 to 1853, Japan closed its borders to international trade. The country existed entirely within its own sphere; its aesthetic principles developed with no influences from the outside. Nor did the outside world have much knowledge about what was happening within the borders of Japan. This all changed when 15-year-old Emperor Meiji fully reestablished trade with the west, and products from Japan suddenly flooded European ports.

Artists were especially drawn to the vivid color palettes and aesthetic differences of Japanese prints. Ukiyo-e, which loosely translates to “pictures of the floating world,” is the name for Japanese woodblock prints that were popular during Japan’s Edo Period (1615-1868). Ukiyo-e artists in 17th and 18th century Japan desired a departure from strict rules and subjects. They created the Ukiyo-e movement to celebrate all that was ephemeral in life – a floating world of springtime and cherry blossoms, happiness, and leisure. The prints were inexpensive to make and relatively easy to reproduce, making Ukiyo-e natural export products to Europe.

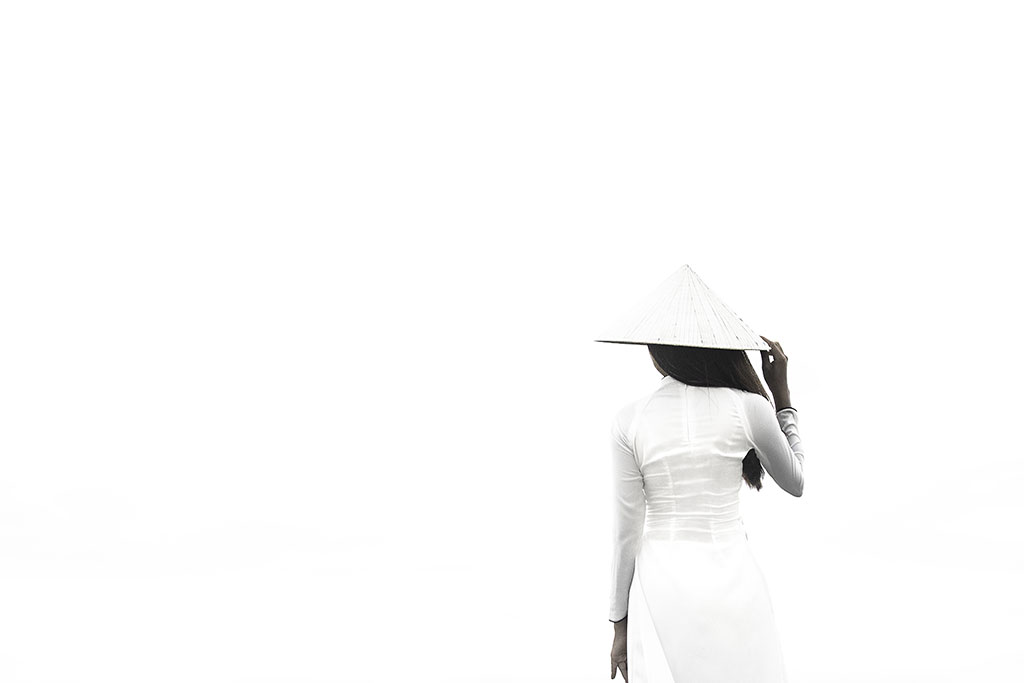

Simplified compositions, textural patterns, empty space, and unusual viewpoints and themes (for European art) also made the prints stand out among fine artists who studied them.

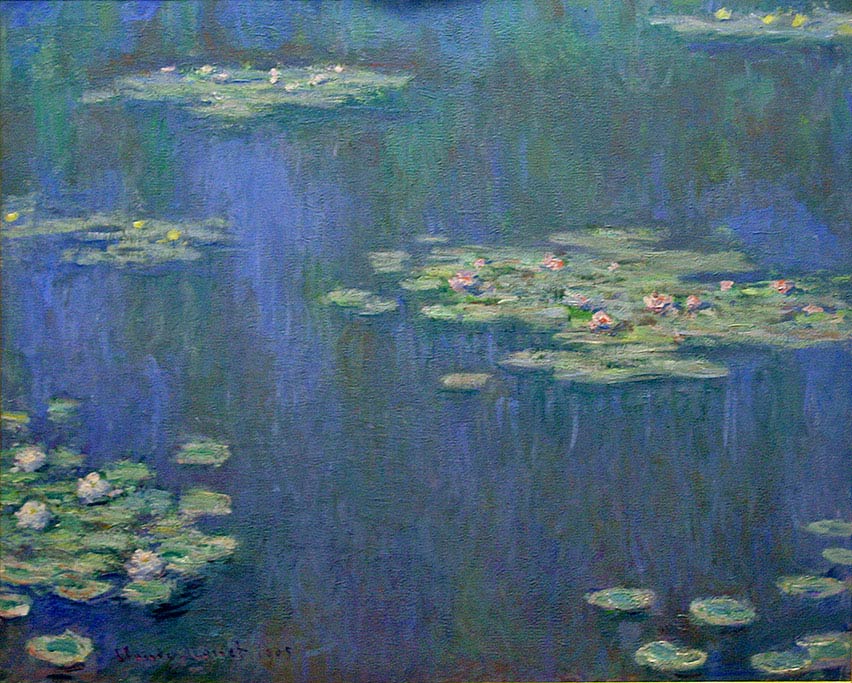

The tranquil pastoral scenes and leisure activities depicted in Ukiyo-e are similar to another art movement that was developing just at the moment that Japan’s relationship with France grew stronger – Impressionism. Characterized by washes of color, softened edges, emotional impact, and symbolism, Impressionistic paintings also resided in a floating world of beauty and shifting light.

The Impressionists and Japonisme

The Impressionist painters strove to depict the ever-shifting effects of light and nature through looser brush strokes and reimagined colors. The invention of the paint tube in 1841 also allowed these artists the freedom to exit their studios and set up their easels on the waterfront or in the center of a field; wherever inspiration struck! This Plein Air style (open air) allowed them to quickly paint the changing scenes, without agonizing over every exact detail.

While Impressionistic paintings may seem tame by today’s standards, the ideas put forward by the Impressionists set off quite a controversy in the Parisian art world at the time. The Académie des Beaux-Arts, an academic art association in Paris, set the rules for what was considered acceptable in French art – mainly focusing on realism and classical subjects such as mythological and historical settings. Next to these works, Impressionist paintings were considered messy and even juvenile. Yet, these works created a strong sensation in the viewer. They have a dreamlike irreality that still appeals to collectors today. In Japonisme, like impressionism, the goal of the artist was to capture the sense of movement rather than adhering to the exact scene.

Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were two of the first Impressionist painters to begin using artistic principles from Japan to reimagine their compositions.

They were inspired by their use of decorative patterns as well as embracing off-center compositions, flat colors, and negative space.

Cassat, Van Gogh, Klimt, Picasso, Modigliani, Munch, Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Gaugin were just a few of the painters whose iconic styles were forged from their inspired use of some of the Japanese design principles that follow:

Perspective in Japonisme

Japanese prints played with perspective, often placing both near and far objects within the same line of sight. The viewer’s eye might be drawn to a very closely cropped subject in the foreground, as well as the horizon or an object in the far distance. Painters have always tried to “break the picture plane” to create the illusion that the canvas or paper is not flat. Japanese print work approached three-dimensionality differently. The works had volume and depth, yet, they remained within the “picture frame,” because of their flat uses of color and line work. What the viewer’s eye perceived of the portrayed scene is an “objective reality” – creating a play between what is actually rendered on the canvas and what is left to the viewer’s imagination.

Another viewpoint is the bird’s eye view. Long before humans created flying machines, Japanese artists had already been imagining aerial perspectives for a millennium. In Japanese, this viewpoint is called fukinuki-yatai, which literally translates to “blown-away roof.” Beyond woodblock prints, fukinuki-yatai was often used to decorate folding screens and hanging kakemono scrolls to give the trompe-l’oeil effect of distance and verticality. Verticality in itself took a starring role in the Japonisme trend. Long panels were used to mimic scrolls and to draw the viewer’s eye upward.

These images also break a common compositional guideline – the rule of 3rds. This rule proclaims that subjects should always be placed in the right or left 3rd of the image so that negative space fills the other 2/3rds of the composition. The technique often follows a grid to compose an image. It is commonly believed that this guideline creates compelling and well-composed artworks. Yet, master painters have been breaking this rule for generations.

Some Japanese artworks moved even further away from the rule of 3rds by boldly centering the subject, removing horizon lines, and even filling the entire print with a subject. These techniques were also adopted by 19th-century artists as they explored Japonisme in their own works.

“It took me one day to learn the Rule of 3rds, but many years to understand that it limits creativity.”

- Réhahn

Cropping

Japanese prints often used a tightly cropped composition to add drama and visual interest to the frame. This style that became so popular in the late 1800s remains an important compositional technique in contemporary art and photography today.

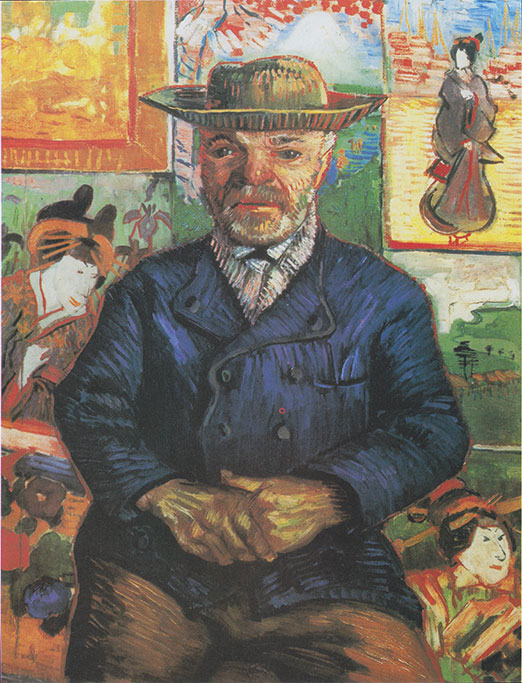

Many of Van Gogh’s portraits used a closely cropped layout to add emotion and style to his compositions. He was also fond of borrowing certain textures and motifs from Japanese art. His portrait of Père Tanguy (1887) shows a close-up of a European man centered in front of a wall covered in traditional Japanese motifs.

Flat Colors

European art prior to the Impressionists was focused on creating a realistic sense of color through the arduous mixing of oil paints and glazes, adding layer upon layer to create nuance and depth. Rarely were pure colors used directly on the canvas without other shades washed over them. In the 19th century, Japanese arts and crafts took a different approach. Large planes of colors were spread across the image to create a flattening effect. Bright tones were used unabashedly, in part because each color also carried its own symbolism. For example, blue might be used to represent the sea and the sky, but also security, purity, and calm.

The use of primary colors for their emotional qualities was explored by the Impressionists, but it really found its place within the works of the Post-Impressionists and Expressionists. Van Gogh’s The Starry Night is a good example of a work that bridges all three styles – Japonisme, Post-Impressionism, and Expressionism.

Tonal artwork, in which only a few colors were used in the finished composition, was also used by other French artists such as Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Georges Seurat. The goal was to create harmony and balance through the chosen colors, without being beholden to reality.

Empty Space

The use of tonal works naturally encompassed the concept of empty or negative space. In Japanese art forms, artists didn’t feel the need to fill the entire canvas in the same way that European artists did. The Japonisme movement followed the idea that empty space was necessary. It gave the work “room to breath” and created impact and interest for the subject.

In addition, Japan is a primarily Buddhist nation. In Buddhism, emptiness doesn’t mean nothingness. Negative space is a way to describe the reality that we, as humans, cannot comprehend everything around us. We even have an emptiness within ourselves, and embracing this emptiness is part of the path toward enlightenment for Buddhists.

“We join spokes together in a wheel, but it is the center hole that makes the wagon move. We shape clay into a pot, but it is the emptiness inside that holds whatever we want. We hammer wood for a house, but it is the inner space that makes it livable.”

- Lao Tzu from Tao Te Ching

Symbolism

One of the most important inclusions in the Japonisme movement is the use of symbolism. Symbols had been used for centuries in European art, often creating a sort of hide-and-seek for those in the know. Renaissance painters used animals or colors to represent social status. In Romantic Art, certain symbols were used to show political dissent. However, during the Japonisme phase in art history, symbolism took a different turn, focusing more on decorative motifs, spirituality, and archetypal imagery.

In the late 1800s, Japanese symbols and motifs appeared everywhere. From Monet’s painting of his wife dressed in a kimono, to Edouard Manet’s painting of the author Emile Zola, in which the subject is framed by a wall of Japanese prints rendered on the canvas. Mary Cassat’s subjects were often ensconced in intricate Asian-inspired textiles, as were Gustaf Klimt’s famous “Golden Ladies.”

Hand fans were an important motif in the works of Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, and later Amedeo Modigliani. Many of these artists even combined arts and crafts with fine art by painting directly on the fans themselves.

Monet’s bridge above his waterlily pond draws obvious similarities to popular Japanese woodblock prints. Reflections also played a large part in his works and those of the other Impressionists and Post-Impressionists such as Mary Cassatt, Pierre August Renoir, and Vincent van Gogh. In Japan, water represents purity, while reflections elicit the concept of “Hansei” or introspection, which is a fundamental part of Japanese culture. Reflections could also evoke the idea of leisure time and tranquility. Flowers and boats skimming the surface of lake, women reflected in their bath water, and the lights of the night sky echoed within a harbor all take the viewer into a space of calm observation.

Natural environments, reflections, flowers, birds, graphic line work, verticalism – all of these elements were also primary inspirations for other artistic and architectural movements such as Art Nouveau and eventually Art Deco.

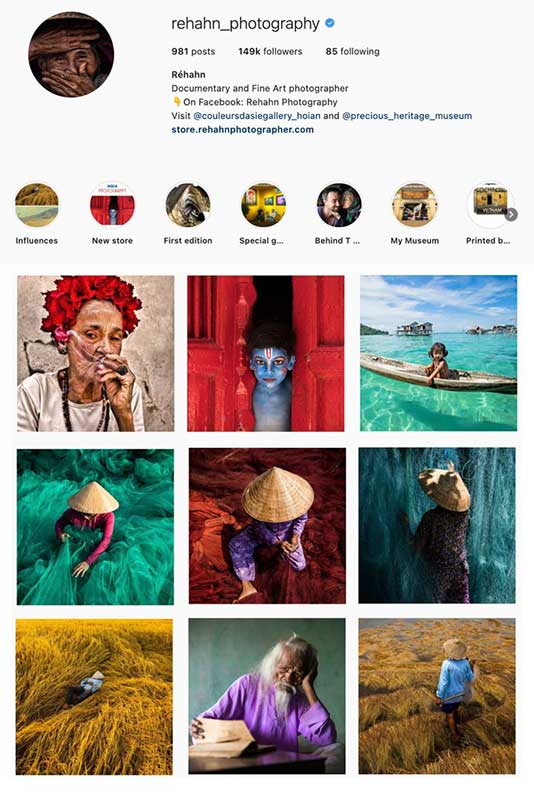

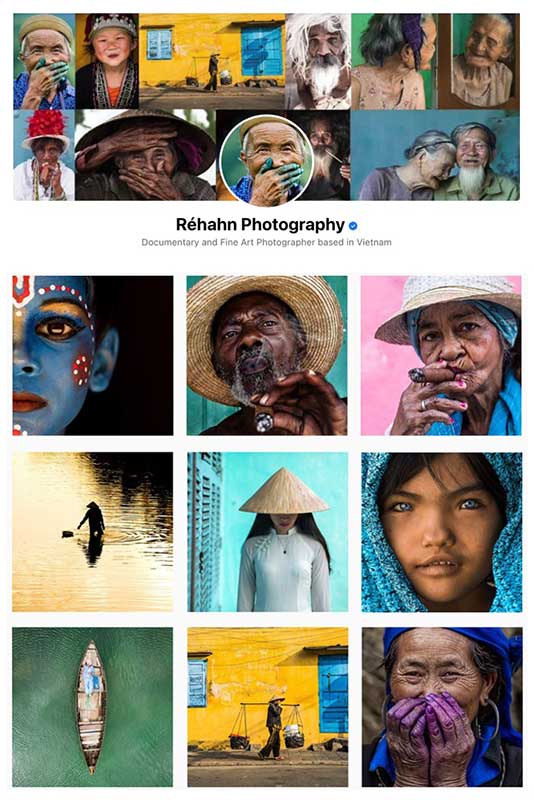

Japonisme’s Role in Réhahn’s Contemporary Art

The influence of Japonisme and Impressionism on Réhahn’s photos isn’t a usurpation of Japanese culture or an artistic movement, instead, it is a transformation of the way the artist approaches his work with respect to new influences, lending layers of depth and history to his images.

The techniques and merging of cultures discovered during the Japonisme era forever changed the worlds of Fine Art, arts and crafts, and architecture to create a new vision of beauty without borders.